While the preponderance of evidence published in the world’s most respected peer-reviewed medical journals clearly shows that a low-fat, plant-based, whole-food diet is the most effective way to prevent and reverse chronic disease, conventional dietary guidelines taught to physicians, dieticians, and patients currently recommend a carbohydrate-restricted diet that contains approximately 35% fat and includes “moderate” amounts of meat, poultry, eggs, cheese, and milk (1–5).

Unfortunately, there is a blatant disconnect between the evidence-based scientific knowledge and current dietary recommendations, which contributes to increasing rates of diabetes, heart disease, cancer, and autoimmune diseases around the world today (3,4,6).

The majority of Americans fear high carb foods, and the majority of mainstream media sources including online news, print newspapers, online magazines, print magazines, and popular blogs eschew high carb foods like fruits, potatoes, and whole grains in favor of the more “trendy” low-carb foods such as plant oils, bacon, and butter.

At Mastering Diabetes, we believe the public deserves to know the truth about high carb foods and their role in reversing insulin resistance, backed by more than 85 years of scientific evidence.

One area of confusion is that not all high carb foods are created equal. We will explain in the third section of this article exactly why refined carbohydrates from added sugars and grains that have been processed into flour have a different metabolic effect on your body than carbohydrates found naturally in whole foods.

But first, we’ll shed light on how a low-carb diet causes insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes, while a low-fat, plant-based, whole-food diet actually reverses this pathology.

Then, we'll present you with some of the more recent studies which contend that animal foods can also worsen insulin resistance and diabetes, as well as reduce your longevity – even if you don’t have diabetes.

Why Low-Fat?

The idea of a low-fat diet may conjure up images of relics of the 1980’s such as Richard Simmons step aerobics on video cassette, late night infomercials selling contraptions that claimed to help you get 6-pack abs quickly and easily, and grocery store shelves lined with “fat-free” cookies, crackers, and chips that basically just tasted like cardboard.

But bear with me here. When we at Mastering Diabetes refer to a “low-fat” diet, we aren’t talking about that type of low-fat diet. Fat-free cookies and their ilk are not on the menu on our plan for optimal nutrition!

There is a specific reason why we emphasize a diet which is composed primarily of high carb foods for preventing and reversing insulin resistance, and if you’ve never heard of this before it may just blow your mind when we tell you about it.

However, we must first investigate the reason why the majority of doctors, dieticians, and patients currently hold the erroneous belief that high carb foods actually cause diabetes rather than reverse it.

Let’s start with the basics.

We’re all taught in grade school about the 3 dietary macronutrients that supply our bodies with calories: carbohydrate, fat, and protein. When you eat any food or beverage that contains carbohydrate, your blood glucose rises.

With the exception of meat, poultry, fish, eggs, butter, and oil, all foods contain carbohydrates.

In people without diabetes, blood glucose is typically somewhere between 70–99 mg/dL before a meal. After a meal containing a large amount of carbohydrates, blood glucose may rise as high as 100 - 160 mg/dL.

With the exception of some highly processed foods such as oil, sweeteners, juices, and sugar sweetened beverages, all foods contain protein. However, protein is found in a much more concentrated amount in foods that don’t contain any carbohydrates: meat, poultry, fish, and eggs.

Protein has a negligible effect on blood glucose, although it can actually lower blood glucose a few hours after it is ingested. This happens because protein stimulates the release of insulin from the pancreas (7,8).

Dietary fat has no immediate effect on blood glucose, nor does it stimulate the release of insulin from your pancreas.

The fact that dietary protein can lower blood glucose a few hours after it is ingested, and the fact that dietary fat has no immediate effect on blood glucose or insulin secretion, has formed the basis for an avalanche of low-carb diet books and bad dietary advice given to people living with diabetes.

But strangely enough, studies show that people who begin to reduce or eliminate their intake of high carb foods like fruit, potatoes, beans, and whole grains in favor of high-protein and high-fat foods, are actually more likely to develop type 2 diabetes than people who eat a lot of carbohydrate and relatively little dietary fat or concentrated forms of protein) (9).

In contrast, people who eat a low-fat, plant-based, whole-food diet actually improve their glucose tolerance and become highly efficient at clearing glucose from their blood.

Populations of people who subsisted on a traditional diet composed primarily of high-carbohydrate whole foods did not begin to experience cases of type 2 diabetes until their diet began to shift away from traditional high-carb foods and towards more high-protein and high-fat foods (10–13).

If carbohydrate is the only macronutrient that actually raises blood glucose, then why do people who eat the most high carb foods have the lowest blood glucose levels?

Why do people who routinely avoid high-carb foods in favor of high-protein and high-fat foods experience the highest blood glucose response when they do eat carbohydrate-containing foods?

This seemingly counterintuitive phenomenon remained a mystery until the late 1970’s when magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was invented by Raymond Damadian, MD. MRI technology made it possible for doctors and scientists to see inside every part of the human body noninvasively.

When this new technology became commercially available in the early 1980’s, scientists began to notice that people with diseases of insulin resistance, such as metabolic syndrome and diabetes, have large amounts of ectopic fat (fat contained in organ tissue and muscle tissue) in comparison with healthy people.

They began to conduct studies showing that when healthy adults are given a meal containing only fat or a meal containing a high amount of fat, the amount of ectopic fat in their muscle tissue rapidly increased within hours of consuming the large amount of fat (14,15).

If a high-fat meal is just an infrequent, one-off event in a healthy person, the ectopic fat that gets stored in their muscle tissue will be used as energy during an intense or prolonged exercise session.

However, if the person repeatedly consumes high-fat meals over a period of a few weeks or longer, the ectopic fat begins to accumulate more and the formerly healthy person develops insulin resistance and eventually, prediabetes and diabetes (16,17).

When a person has developed insulin resistance, when high-carb foods are consumed, blood glucose can rise well above 160 mg/dL.

In contrast, when you consistently eat a maximum of 15% of your total calories as fat, only small amounts of fatty acids are stored in organ and muscle tissue, allowing cells in both depots to remain responsive to insulin when it appears.

This is great news, because when your insulin sensitivity is high, it is much easier to control your blood glucose after eating high carb foods.

In the context of a low-fat, plant-based, whole-food diet, the more high-carb foods you eat, the more insulin sensitive you become. And this is why eating this way can prevent and reverse type 2 diabetes, as well as decrease insulin requirements in type 1 and type 1.5 diabetes.

So why does storing ectopic fat in organs and muscle tissue cause high blood glucose after eating high carb foods?

Let’s go back to biology 101. When you eat carbohydrates, your digestive system breaks these carbohydrate chains into smaller monosaccharide molecules, and these monosaccharide sugars then enter your blood, causing your blood glucose to rise.

Your pancreatic beta-cells sense this rise in blood glucose, and then secrete insulin to tell tissues to uptake glucose. Think of insulin as an escort that tells peripheral tissues, “Hey! I have some glucose. Do you want to take some and get energy?”

Insulin’s primary job is to escort glucose out of your blood and into your brain, muscles, and liver. When insulin’s ability to communicate with these tissues is compromised, glucose remains trapped in your blood, causing high blood glucose.

When excess fat is stored in organs and muscle, these fatty acids stimulate a series of intracellular reactions that inhibit insulin from allowing glucose to enter (14).

As a result, glucose accumulates in your blood, and your brain and body tissues become starved for fuel. You may experience symptoms such as lethargy, brain fog, hunger, and excessive thirst.

The good news is that you can get rid of excess ectopic fat in muscles and organs using a low-fat, plant-based, whole-food diet, combined with physical exercise. When insulin is effective at communicating with tissues, you gain the ability to eat high-carb foods like fruit, potatoes, beans, and whole grains without experiencing high blood glucose levels.

When your brain and muscles have an adequate supply of high-quality fuel (glucose), you feel good. You have an abundance of energy and are able to think clearly with no brain fog.

Why Plant-Based?

Now you may be wondering: “If the consumption of excess dietary fat exacerbates insulin resistance and causes type 2 diabetes, and if protein has a slightly blood glucose lowering effect, then what’s wrong with eating a high-protein diet?”

In theory, a high-protein diet seems like a logical solution for managing blood glucose, and mountains of diet books advocate a high-protein diet for everything from weight loss to bodybuilding.

Some evidence demonstrates that dietary protein has a negligible effect on your blood glucose, and that it can actually lower blood glucose a few hours after you eat a high-protein meal. This happens because protein stimulates the release of insulin from your pancreas (7,8).

However, when a high protein diet is actually put to the test, it worsens insulin sensitivity rather than improving it. How do we know this?

Because a growing body of evidence shows that eating a single high-protein meal causes dramatic blood glucose excursions for up to 5 hours after the meal (18).

In addition, even when people lose 10% of body weight following a reduced-calorie, high-protein diet, eating a high-protein diet eliminates the expected increase in blood glucose control normally seen just due to weight loss.

In other words, losing weight is one of the most powerful ways to increase your insulin sensitivity, but eating a diet high in protein prevents this from occurring (19–21).

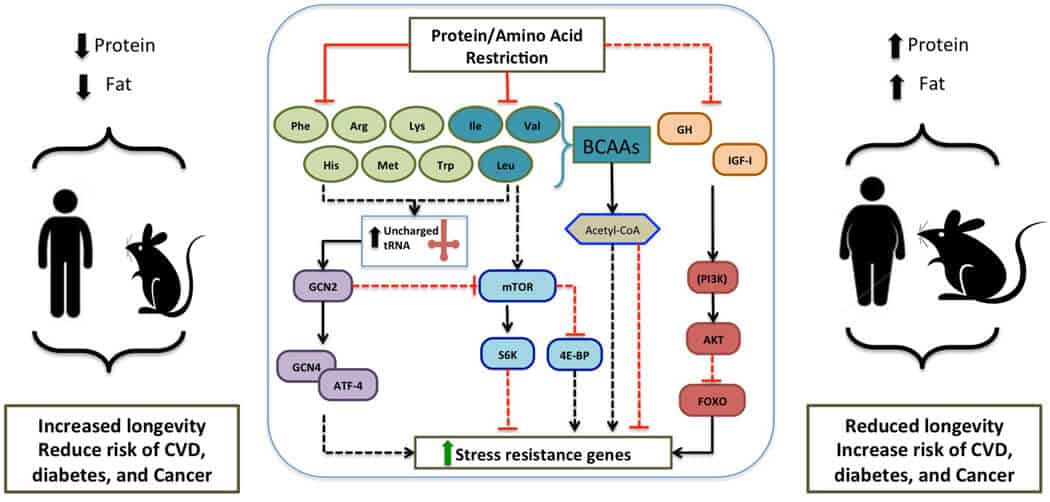

Even more alarming, scientists are now discovering that diets high in animal-based forms of protein can actually shorten lifespan and significantly increase your risk for premature death (2,22,23).

In contrast, protein found in whole plant-based foods such as beans, lentils, peas, whole grains, vegetables, potatoes, and fruit does not increase mortality risk, and is instead associated with increased lifespan and healthspan (2,22).

Why Whole Foods?

When many people hear the words low-fat and plant-based uttered in the same sentence, they don’t hear the “whole-food” end of the sentence.

Many people comment, “No, I can’t eat that. Without eating some fatty foods, I’m going to be hungry all the time!”

One simple and powerful secret to achieving and maintaining your ideal body weight without feeling deprived or unsatisfied after meals is to eliminate processed foods from your diet and eat as many whole foods as possible.

One reason why most people struggle to achieve lasting weight loss on a conventional low-fat or plant-based diet is because they often eat significant quantities of processed vegan foods, which have been specifically engineered to bypass two crucial satiety mechanisms (24–26):

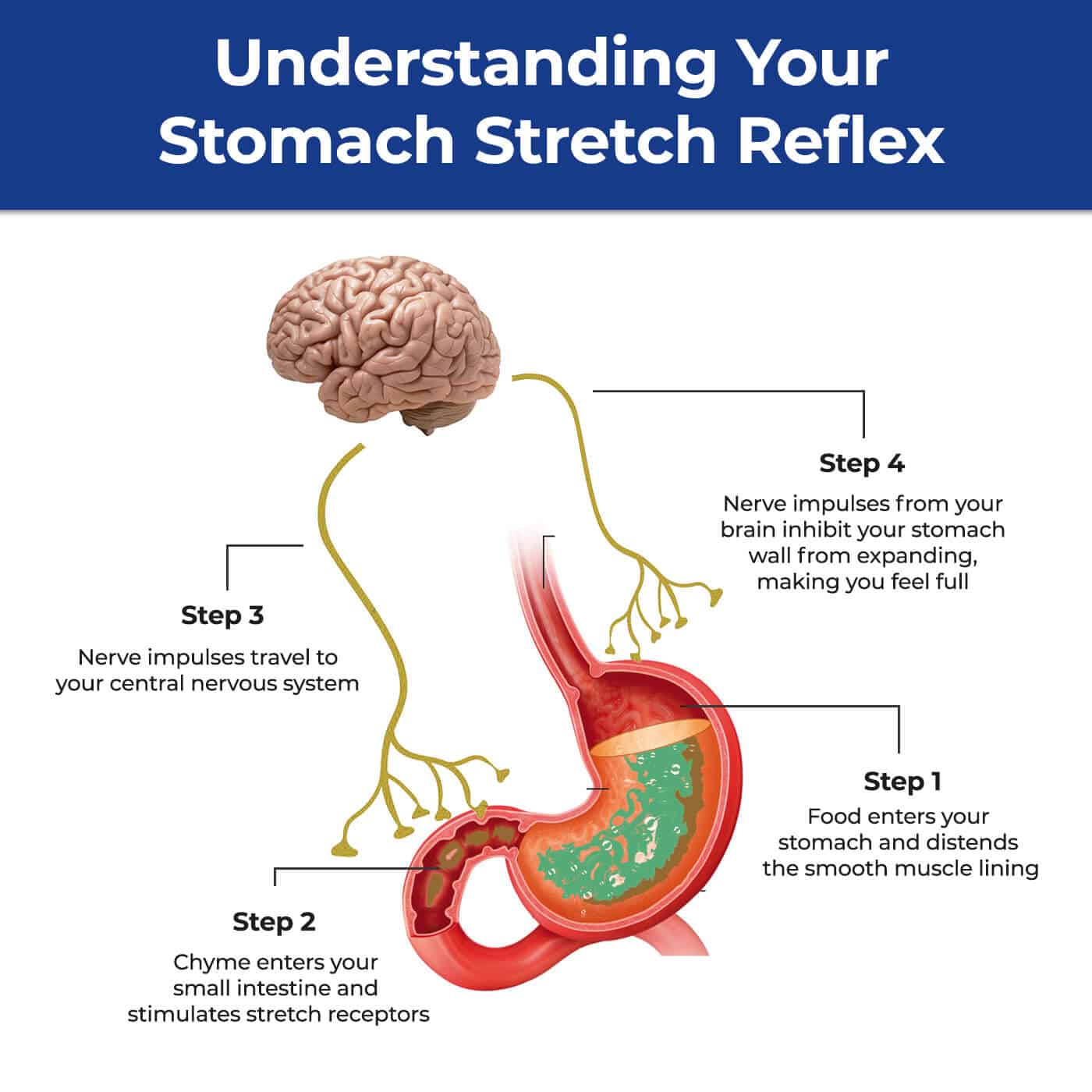

When you eat whole foods, both your sensory specific satiety and stomach stretch reflex are triggered to send a neurological signal to your brain that says, “I feel satisfied and full.”

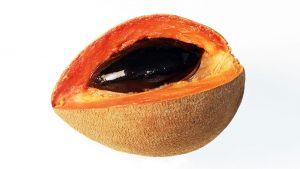

Sensory specific satiety occurs most notably when you eat a naturally sweet whole food such as dates, jackfruit, or mamey sapote. After you’ve eaten a few bites, the sweetness begins to not taste as good as it did on the first bite. You begin to feel satisfied when you’ve received a necessary amount of nutrition from these high carb whole foods (27).

As long as you’re not eating too quickly and you’re taking the time to chew and taste these foods, your sensory specific satiety mechanism will help you know when you’ve had enough of a particular flavor or nutrient (28).

Sweet processed foods such as candy bars, cookies, and cakes contain other non-sweet ingredients such as salt, fat, and sometimes even chemical flavor enhancers or appetite stimulants.

Savory processed foods often contain non-savory ingredients including sugar, monosodium glutamate, artificial colors, artificial flavors, and emulsifiers to stimulate your appetite and keep you wanting more.

This magic combination of multiple contrasting flavors is specifically designed to bypass your sensory specific satiety, so that you are more likely to eat more calories than you need, and eat meals or snacks more frequently (26).

The stomach stretch reflex is your other predominant satiety mechanism. When you eat a meal, stretch receptors in the walls of your stomach are activated. As the amount of food in your stomach increases, these stretch receptors send a signal to your brain to reduce your appetite. As your stomach stretches past a certain point, it becomes uncomfortable for you to continue to eat.

Processed foods tend to be more calorie-dense than whole foods because they lack intact fiber and water. Because of this, it is easier to eat thousands of unnecessary calories before your stomach sends a signal to your brain that says, “Slow down!” or “I’m full!.”

In addition, low-fiber or no fiber processed foods leave your stomach fairly quickly (especially if they are low-fat processed foods), which means you’ll feel like eating again within a short amount of time.

Whole foods not only contain intact fibers and a higher water content than processed foods, but they are also less calorie-dense. You could eat apples, broccoli, beans, or boiled potatoes until you feel absolutely stuffed – and you would still not consume too many calories.

Although food manufacturers often add fiber to packaged foods, these added fibers act differently from the intact fiber found in whole foods. Added fiber has been hydrolyzed and processed significantly, resulting in shorter cellulose chains that do not make you feel as full.

When you switch to a low-fat, plant-based, whole-food diet like we recommend, you will likely need to eat a lot more food than you think – even if you’re trying to lose weight.

Even the more calorie-dense low-fat, plant-based, whole foods such as sweet fruits, potatoes, beans, and whole grains have less calorie density than most of the high-fat, processed foods you’re accustomed to eating.

Just to maintain your weight, the portion sizes of your meals will need to be double, triple, or more than the portion sizes of high-fat and processed foods.

The High Carb Foods Master List

The list of high carb foods included below is divided into green light foods and yellow light foods.

Green light foods can be eaten ad libitum – without restriction – until you are comfortably full. There is no need to control your intake of green light foods because your innate stomach stretch reflex satiety mechanism should prevent you from eating more calories than your body needs.

Yellow light foods tend to be more calorie dense than green light foods, and because of that we recommend eating them in smaller quantities. In addition, we encourage you to eat yellow light foods slowly to activate your sensory specific satiety mechanism and prevent you from excess calories.

Use the list of high carb foods below as your encyclopedia of low-fat, plant-based, whole-foods. If you’re curious about what foods are in each category, scroll down to see which fruits, vegetables, legumes, and whole grains are included in the Mastering Diabetes Program.

The list below is sorted in order of decreasing calorie density. This is your chance to open your mind to the power of high carb foods (from whole sources) and experience the true power of a low-fat, plant-based, whole-food diet!

FRUITS

Mamey Sapote

563 Calories Per Pound

Plantains

554 Calories Per Pound

Persimmons

477 Calories Per Pound

Breadfruit

468 Calories Per Pound

Custard Apple

459 Calories Per Pound

Passionfruit

440 Calories Per Pound

Jackfruit

430 Calories Per Pound

Sugar Apple

427 Calories Per Pound

Bananas

404 Calories Per Pound

Pomegranate

377 Calories Per Pound

Sapodilla

377 Calories Per Pound

Jujube

359 Calories Per Pound

Crabapples

345 Calories Per Pound

Cherimoya

341 Calories Per Pound

Figs

336 Calories Per Pound

Elderberries

331 Calories Per Pound

Kumquats

322 Calories Per Pound

Grapes

313 Calories Per Pound

Guavas

309 Calories Per Pound

Lychees

300 Calories Per Pound

Soursop

300 Calories Per Pound

Kiwi

277 Calories Per Pound

Longans

272 Calories Per Pound

Mangos

272 Calories Per Pound

Quinces

259 Calories Per Pound

Red and White Currants

254 Calories Per Pound

Tangerines

241 Calories Per Pound

Raspberries

236 Calories Per Pound

Pineapple

232 Calories Per Pound

Apricots

218 Calories Per Pound

Loquats

213 Calories Per Pound

Clementines

213 Calories Per Pound

Cranberries

209 Calories Per Pound

Plums

209 Calories Per Pound

Gooseberries

200 Calories Per Pound

Nectarines

200 Calories Per Pound

Horned Melon

200 Calories Per Pound

Blackberries

195 Calories Per Pound

Mulberries

195 Calories Per Pound

Papayas

195 Calories Per Pound

Grapefruit

190 Calories Per Pound

Asian Pears

190 Calories Per Pound

Prickly Pears

186 Calories Per Pound

Peaches

177 Calories Per Pound

Pommelo

173 Calories Per Pound

Honeydew Melons

163 Calories Per Pound

Cantaloupe Melons

154 Calories Per Pound

Strawberries

145 Calories Per Pound

Carambola (Starfruit)

140 Calories Per Pound

Watermelons

136 Calories Per Pound

Casaba Melons

127 Calories Per Pound

STARCHY VEGETABLES

Cassava (Yuca)

731 Calories Per Pound

Taro

645 Calories Per Pound

Yams

527 Calories Per Pound

Russet Potatoes

440 Calories Per Pound

Corn

436 Calories Per Pound

White Potatoes

427 Calories Per Pound

Acorn Squash

254 Calories Per Pound

Hubbard Squash

227 Calories Per Pound

Carrots

186 Calories Per Pound

Butternut Squash

182 Calories Per Pound

Spaghetti Squash

127 Calories Per Pound

BEANS, PEAS AND LENTILS

Chickpeas

745 Calories Per Pound

Pink Beans

677 Calories Per Pound

Pinto Beans

649 Calories Per Pound

Small White Beans

645 Calories Per Pound

Navy Beans

636 Calories Per Pound

Cranberry Beans

617 Calories Per Pound

Black Beans

599 Calories Per Pound

French Beans

586 Calories Per Pound

Adzuki Beans

581 Calories Per Pound

Kidney Beans

577 Calories Per Pound

Pigeon Beans

549 Calories Per Pound

Great Northern Beans

536 Calories Per Pound

Split Peas

536 Calories Per Pound

Moth Beans

531 Calories Per Pound

Lentils

527 Calories Per Pound

Lima Beans

522 Calories Per Pound

Broad Beans

499 Calories Per Pound

Mung Beans

477 Calories Per Pound

Green Peas

381 Calories Per Pound

Fava Beans

281 Calories Per Pound

Yardlong Beans

213 Calories Per Pound

Yellow Beans

159 Calories Per Pound

Green Beans

159 Calories Per Pound

INTACT WHOLE GRAINS

Wheat (Kamut)

599 Calories Per Pound

Spelt

577 Calories Per Pound

Barley

558 Calories Per Pound

Brown Rice

558 Calories Per Pound

Quinoa

544 Calories Per Pound

Millet

540 Calories Per Pound

Rye

500 Calories Per Pound

Sorghum

500 Calories Per Pound

Wheat (Red Winter)

500 Calories Per Pound

Amaranth

463 Calories Per Pound

Wild Rice

459 Calories Per Pound

Teff

459 Calories Per Pound

Buckwheat

418 Calories Per Pound

Bulgar

377 Calories Per Pound

NON STARCHY VEGETABLES

Mountain Yam

372 Calories Per Pound

Shallots

327 Calories Per Pound

Artichokes

241 Calories Per Pound

Broccoli

159 Calories Per Pound

Eggplant

159 Calories Per Pound

White Button Mushrooms

154 Calories Per Pound

Oyster Mushrooms

150 Calories Per Pound

Tomatillos

145 Calories Per Pound

Red Bell Peppers

141 Calories Per Pound

Fennel

140 Calories Per Pound

Rutabaga

136 Calories Per Pound

Kohlrabi

132 Calories Per Pound

Chayote

109 Calories Per Pound

Cabbage

104 Calories Per Pound

Cauliflower

104 Calories Per Pound

Radicchio

104 Calories Per Pound

Okra

100 Calories Per Pound

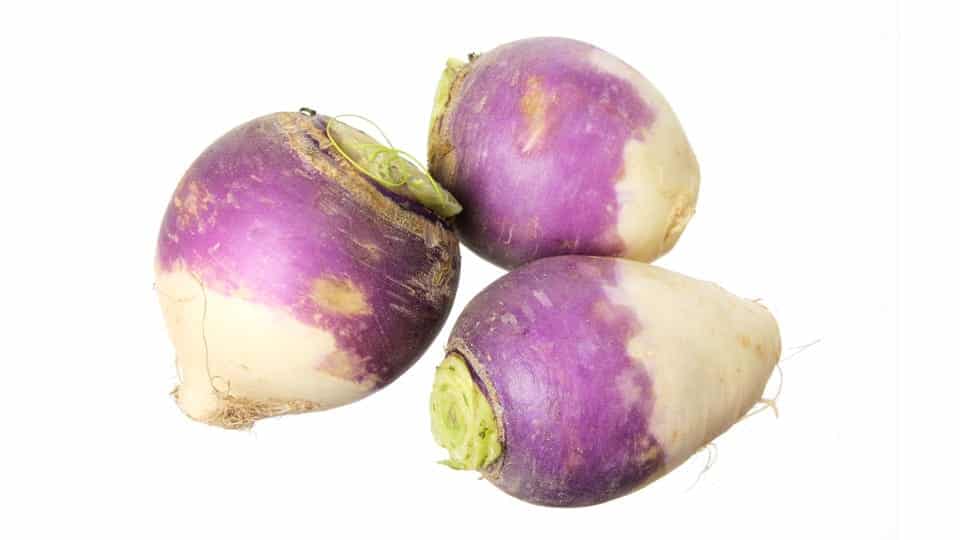

Turnips

100 Calories Per Pound

Rhubarb

95 Calories Per Pound

Asparagus

91 Calories Per Pound

Tomatoes

82 Calories Per Pound

Summer Squash

77 Calories Per Pound

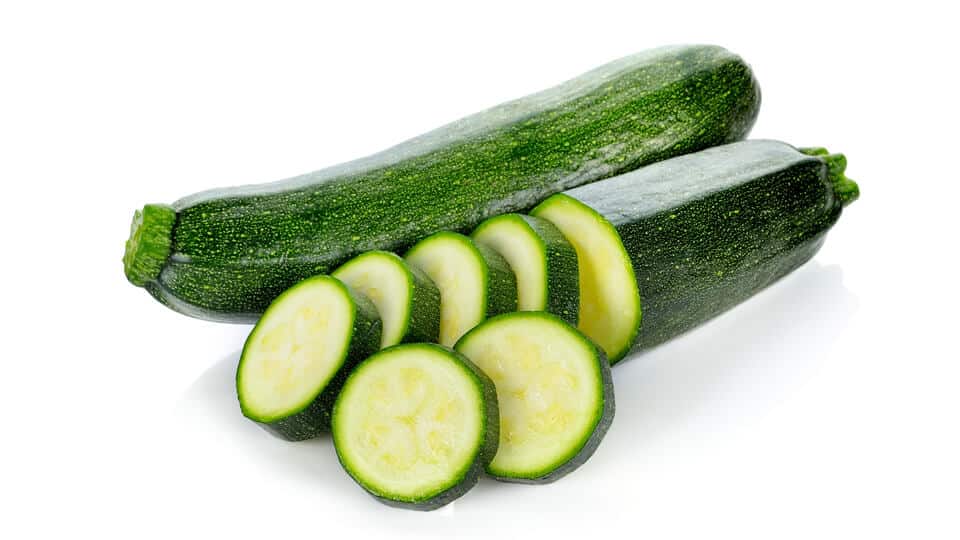

Zucchini

77 Calories Per Pound

Celery

73 Calories Per Pound

LEAFY GREENS

Dandelion Greens

204 Calories Per Pound

Seaweed

195 Calories Per Pound

Parsley

163 Calories Per Pound

Collard Greens

150 Calories Per Pound

Turnip Greens

145 Calories Per Pound

Leeks

141 Calories Per Pound

Chives

136 Calories Per Pound

Kale

127 Calories Per Pound

Green Onions

122 Calories Per Pound

Mustard Greens

118 Calories Per Pound

Arugula

114 Calories Per Pound

Spinach

104 Calories Per Pound

Beet Greens

100 Calories Per Pound

Chard

91 Calories Per Pound

Pokeberry Shoots

91 Calories Per Pound

Purslane

91 Calories Per Pound

Swiss Chard

86 Calories Per Pound

Endive

77 Calories Per Pound

Romaine Lettuce

77 Calories Per Pound

Red Leaf Lettuce

73 Calories Per Pound

Green Leaf Lettuce

68 Calories Per Pound

Nopales

68 Calories Per Pound

Nopales

Iceberg Lettuce

64 Calories Per Pound

Nopales

Butterhead Lettuce

59 Calories Per Pound

Watercress

50 Calories Per Pound

HERBS AND SPICES

NUTS AND SEEDS

Macadamia Nuts

3260 Calories Per Pound

Pecans

3137 Calories Per Pound

Pine Nuts

3055 Calories Per Pound

Brazil Nuts

2992 Calories Per Pound

English Walnuts

2969 Calories Per Pound

Hazelnuts

2933 Calories Per Pound

Sunflower Seeds

2810 Calories Per Pound

Black Walnuts

2810 Calories Per Pound

Sesame Seeds

2601 Calories Per Pound

Pistachio Nuts

2542 Calories Per Pound

Hemp Seeds

2511 Calories Per Pound

Cashew Seeds

2511 Calories Per Pound

Flax Seeds

2424 Calories Per Pound

Chia Seeds

2206 Calories Per Pound

Coconut Meat

1607 Calories Per Pound

Chestnuts

695 Calories Per Pound

YELLOW LIGHT FOODS

Dates

1064 Calories Per Pound

Natto

958 Calories Per Pound

Mature Soybeans

781 Calories Per Pound

Avocado

730 Calories Per Pound

Durian

667 Calories Per Pound

Green Soybeans

640 Calories Per Pound

Edamame

549 Calories Per Pound

References

Lower Your A1c and Get to Your Ideal Body Weight ... Guaranteed

Your results are guaranteed. Join more than 10,000 ecstatic members today

Personalized coaching puts you in immediate control of your diabetes health, helps you gain energy, improves your quality of life, and reduces or eliminates your meds.

Leave a Comment Below

What are your favorite foods from the ones listed above? Leave a comment below and let us know what you're excited to eat.