Are eggs healthy for people with diabetes? Or are they problematic?

On the internet, you'll find tons of people asking these questions, questions like"Are eggs good for diabetics?", "Are eggs BAD for diabetics?", "What about boiled eggs for diabetics, or egg yolks?", "What are the BEST eggs for diabetics?".

And it's clear that most people don't really know. Some people will tell you that eggs will help you keep your blood glucose (blood sugar) low and that a high-egg diet is a healthy diet. But the scientific research says that eggs actually worsen your blood glucose control and may actually exacerbate insulin resistance when eating regularly.

So what's the real hard-boiled truth about eating eggs? That's the question. In this article, we're going to show you exactly what the research says, so that there's no question as to whether or not eggs should be in your diet.

Breaking Down the Confusion Around Eggs

Now in today's article, we want to discuss something very important, because there's a lot of confusion about whether or not eggs are healthy for you and whether you should eat them at all. And if so, whether you should be eating one a day, two a day, three a day, or just a few per week. How do eggs fit into a healthy and nutritious diet? Everyone wants to know.

And yet, there doesn't seem to be a very consistent answer. When you look on social media, a lot of people are confused. And as a result of that, it can be hard to know the actual truth and whether or not eggs should be a part of your diet.

Why The Debate on Eggs Is So Fervent and Muddled

Now, part of the reason that eggs are so popular is that they're actually a relatively inexpensive source of animal protein. They're also a good source of B vitamins. And they also contain a significant amount of iron. But they're also high in cholesterol, and they're high in saturated fat.

And the research demonstrates that foods that contain saturated fats and foods that contain cholesterol are actually causative in increasing your LDL cholesterol, which is the “bad cholesterol.” So we're going to get into detail about that.

Some Background on American Egg Consumption

Now, Americans have actually been consuming fewer eggs since the 1970s, when the research first showed that cholesterol levels in your blood were linked with the development of cardiovascular disease and that eggs could contribute to an increase in your LDL cholesterol.

On the other hand, there are a lot of people who are recommending that people with diabetes don't eat carbohydrate-rich foods, because they say “if you eat carbohydrate-rich foods, then that's going to spike your blood glucose.”

And one of the things that you can do to lower your carbohydrate intake is you can add in other foods that are both protein-rich and fat-rich. So eggs are the perfect food to put in your diet if you're trying to eat a low-carbohydrate diet, right?

Getting to the Bottom of These Studies

Data from controlled studies and large-scale epidemiological studies have actually failed to find a clear association between dietary cholesterol intake and blood cholesterol levels. The research from the 1970s is different from the research conducted in the 1990s because as new research was done, the recommendations were modified.

So in today's world, it can be very confusing trying to determine whether or not eggs contribute to increased cholesterol, whether cholesterol increases cardiovascular disease risk, and whether this has implications for increased diabetes risk.

The confusion about whether eggs are good for you stems mainly from the confusion about whether cholesterol itself is good for you because you can't really separate the two of them. It's hard to decouple them. And that's one of the reasons why so many people are confused.

Probing a Little Deeper into Eggs

Okay, but the question that we're trying to answer is actually more specific than “are eggs good?” For me, it's not that simple. The question that we are trying to answer is even more in-depth, which is “are eggs good for you if you're living with any form of diabetes?”

And in order to answer that question, we’ve got to dive deep into the research, because that's where you're going to find the actual truth. There's actually a very clear difference between what happens to people who eat eggs, who are living with diabetes, and who are not living with diabetes, and we're going to see exactly what that is.

Addressing What You Might Have Already Heard

Now, the last thing I'll say to this is that there are many social media influencers who talk about the fact that you should eat more eggs, and you should eat more protein-rich food, and you should eat more fat-rich food.

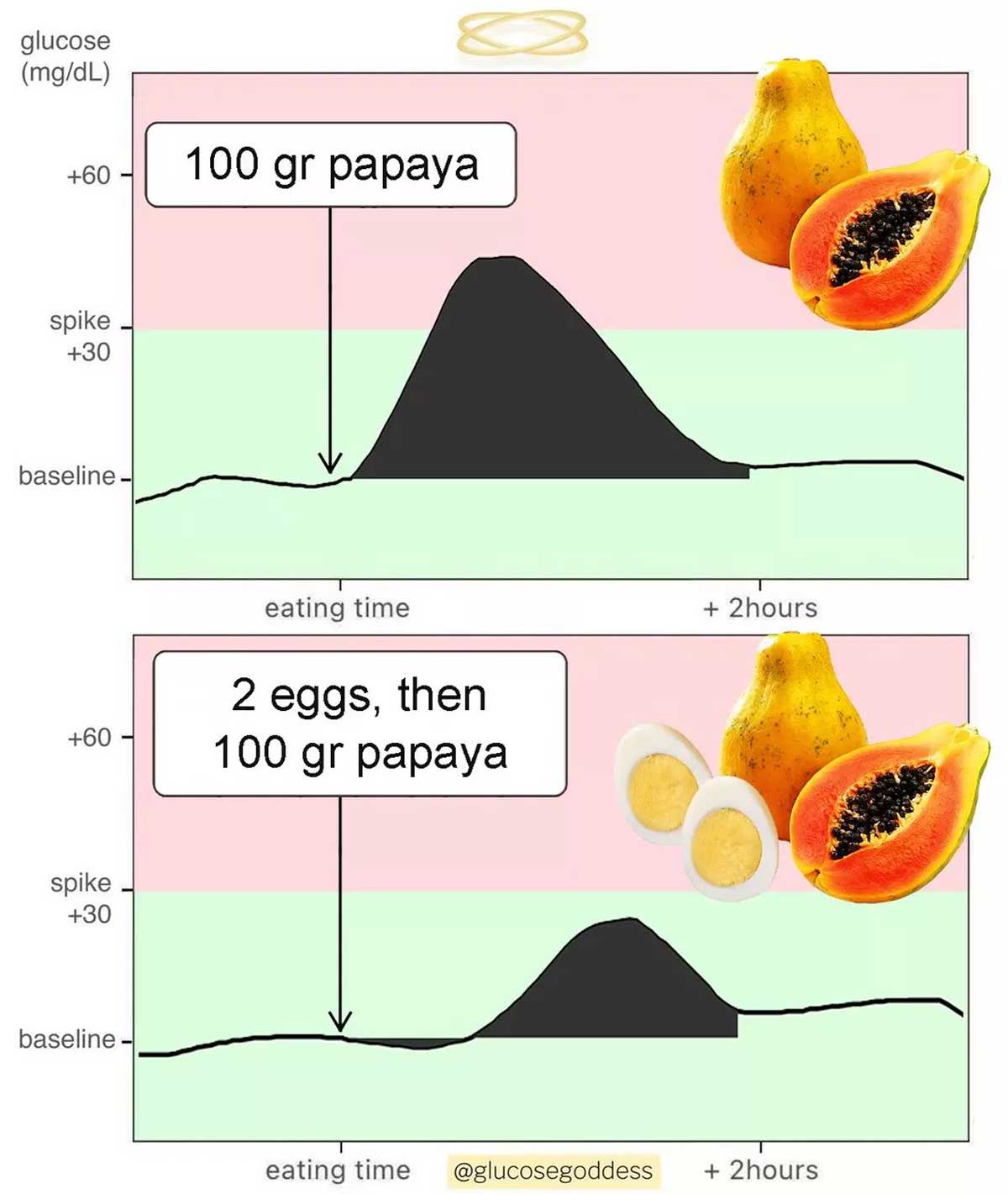

And they'll actually show you images like you see on the screen right here, which indicate that when you add eggs to your meals if you're living with diabetes, you can actually blunt a post-meal blood glucose spike.

So you can see here in the top panel that if you just 100 grams of papaya by itself, your blood glucose can get elevated by about 40 points. But if you add two eggs to that same meal, then your blood glucose doesn't rise as much. And that's generally considered a good thing.

The problem is that this type of thinking is short-sighted because what it forces you to do is focus on the short-term, and ask the question, “what is my blood glucose doing in the next two to three hours?”

But focusing on the short-term benefits only and neglecting the long-term consequences of increasing your protein and fat intake actually will increase your risk for the development of insulin resistance and high blood glucose.

Humpty Dumpty | Breaking Down an Egg

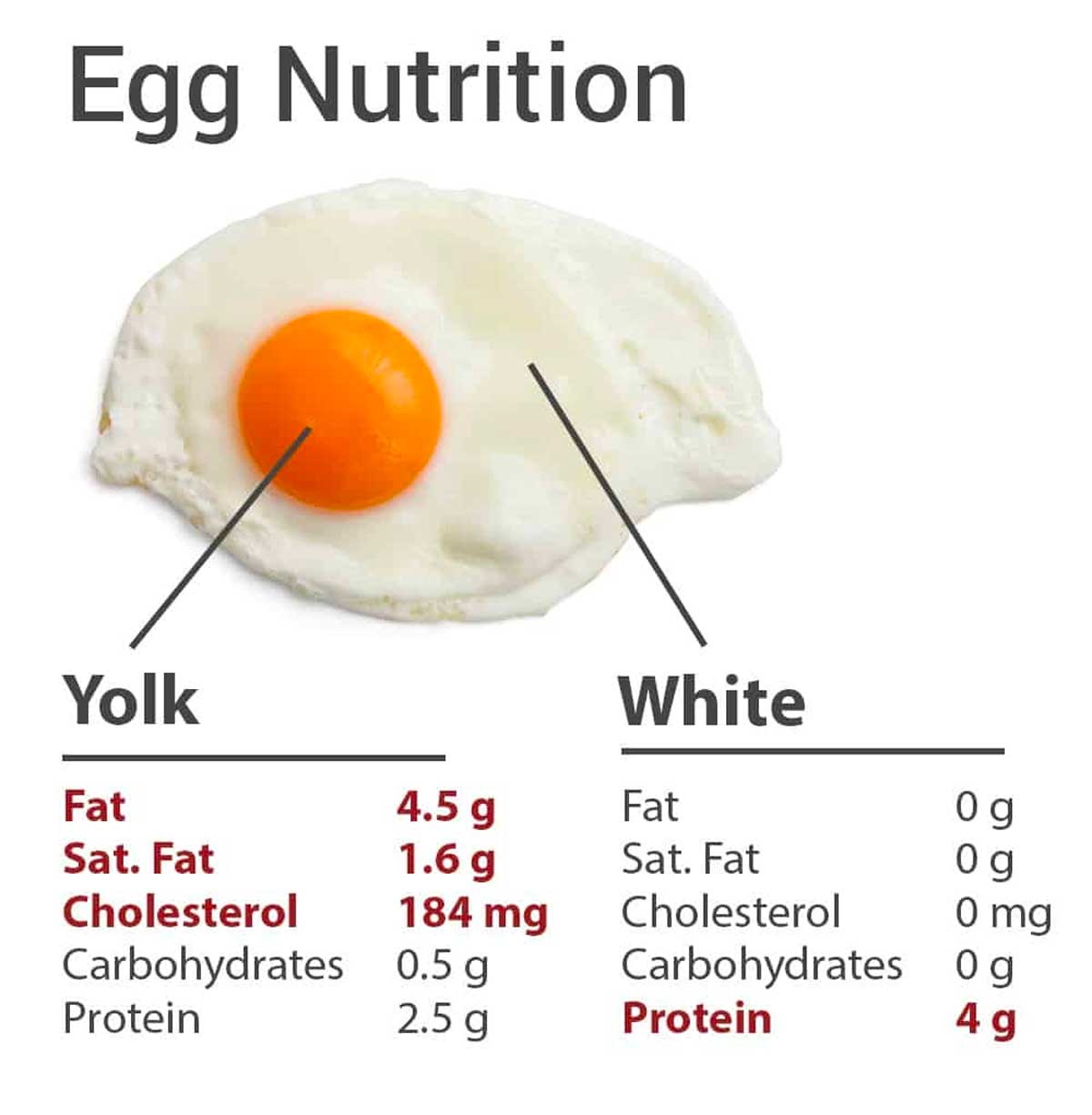

There are two parts of an egg that are distinctly different from one another. The first is the yolk and the second is the white. In order to understand the egg a little bit more deeply, let's understand the nutritional difference between both of those parts.

Now the yolk itself is a storehouse of cholesterol and saturated fat, and it also contains some fat-soluble vitamins and minerals. One egg yolk contains 55 calories, which is 4.5 grams of total fat, 1.6 grams of saturated fat, 184 milligrams of cholesterol, and small amounts of vitamin A, vitamin D, vitamin B6, and vitamin B12.

The egg white is mainly a storehouse of protein. One egg white contains 17 calories. It contains zero grams of total fat, zero grams of saturated fat, zero milligrams of cholesterol, zero grams of carbohydrate, and about 4 grams of protein.

In order to fully understand egg nutrition facts, we have to back up one more time and ask a simple question which is “how do eggs affect both your short-term disease risk and your long-term disease risk?”

It’s important to care about what happens to you in the short term, but even more so about what happens to you in the long term. Certainly, you want to make sure that you're doing things that are going to control your blood glucose and your cholesterol level right now and today.

But what you do today affects your risk for heart disease and diabetes and cancer down the road. By understanding the metabolic effects of eating eggs, you're going to gain insight into how eggs actually increase or reduce your risk for chronic disease.

Cracking into the Data | What the Research Tells Us

Now adults with diabetes, whether it's type 1 or type 2, are two to four times more likely to develop heart disease or stroke than nondiabetic adults, period, end of the story.

The reason for this is simple: elevated blood glucose increases the risk for all forms of cardiovascular disease, including a heart attack, a stroke, angina, and coronary artery disease.

The next question to ask is this: “Do eggs increase the risk of cardiovascular disease or death from diabetes? The only way that you can analyze these results is by looking at multiple different types of research studies.

A Word on Different Study Types, And How They’re Useful in Understanding Eggs

Epidemiology is a type of research that refers to large-scale research that's conducted in large numbers of people over long time scales.

Many people on social media claim that epidemiological research is low quality because they rely on food frequency questionnaires (FFQs) which are questionnaires that ask people questions like, “How many eggs did you eat on average last month?” “How many did you eat last year?” “How many did you eat in the last three years?”

Now, the reason why those questions are fraught with error is because most people can't even remember what they ate for breakfast last Friday. So asking people to estimate how many eggs they ate months or years ago is notoriously inaccurate.

But when you perform studies on thousands of free-living humans living in their home environment, there's really no other way to conduct high-quality research.

That's exactly why researchers perform smaller-scale studies, in which they carefully control the number of eggs that they provide to subjects in addition to epidemiological research. Controlled studies allow you to carefully watch, measure, and record egg intake with precision.

Nevertheless, large-scale epidemiological studies have a time and a place. They're helpful in understanding the trends that occur in large samples of the population over large time scales, which is usually more than 5 years.

The trick here is to combine the epidemiological results with small-scale interventional data. This gives you an opportunity to understand whether there's a commonality between small-scale and large-scale research.

A Deep Dive into the Research

Study 1 – A Prospective Study of Egg Consumption and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease in Men and Women

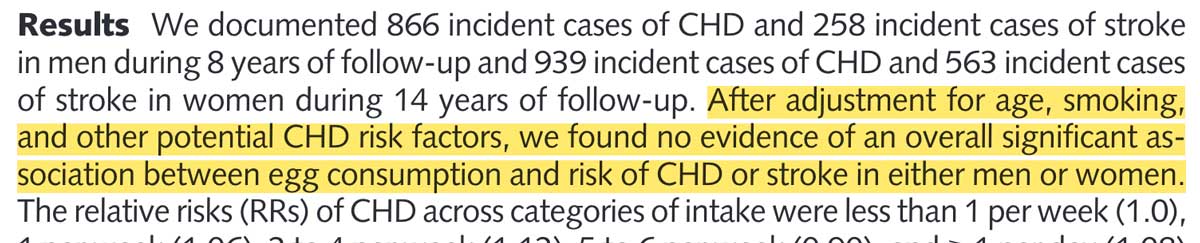

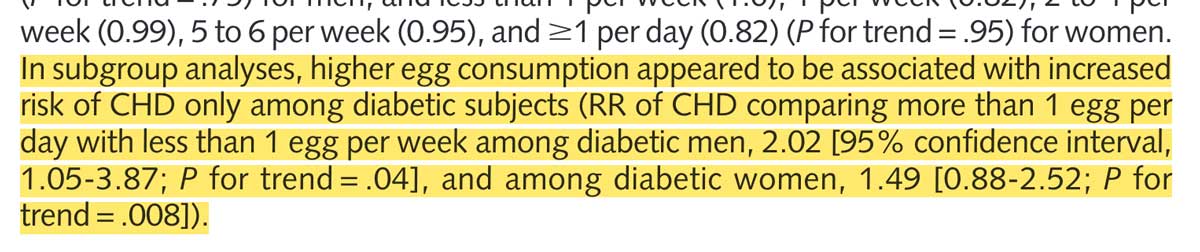

The first paper was published in 1999, and it analyzed the health outcomes of more than 37,000 men aged 40 to 75 years and more than 80,000 women aged 34 to 59. The researchers found that after adjusting for age, smoking, and other cardiovascular risk factors that contribute to coronary heart disease, they found no evidence of a significant association between egg consumption and the risk of coronary heart disease or stroke in either men or women.

The researchers concluded that eating 6 or more eggs per week has zero measurable effect on an increased risk of coronary heart disease.

And these are the types of studies that the general public cites and says, “hey, look eggs are good for you! And I can prove it because that paper just demonstrated that there's no negative effect from eating up to 6 eggs per week.”

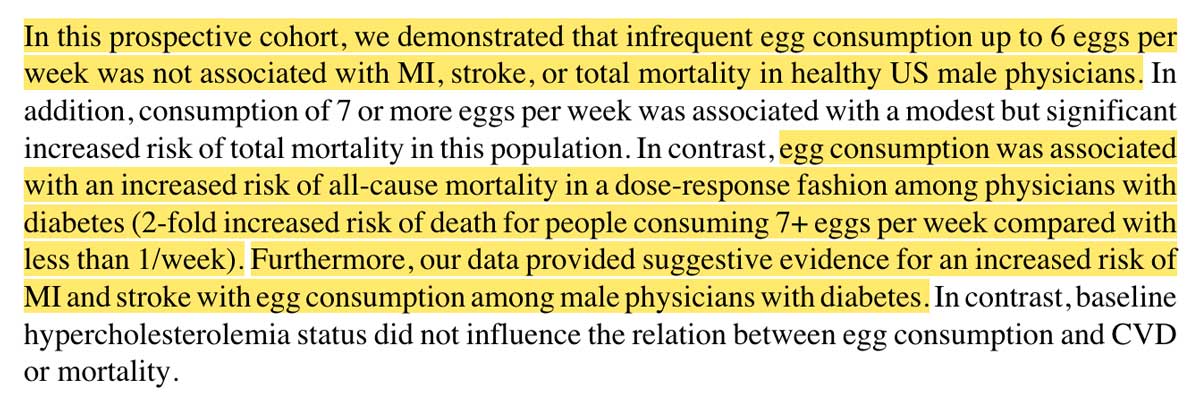

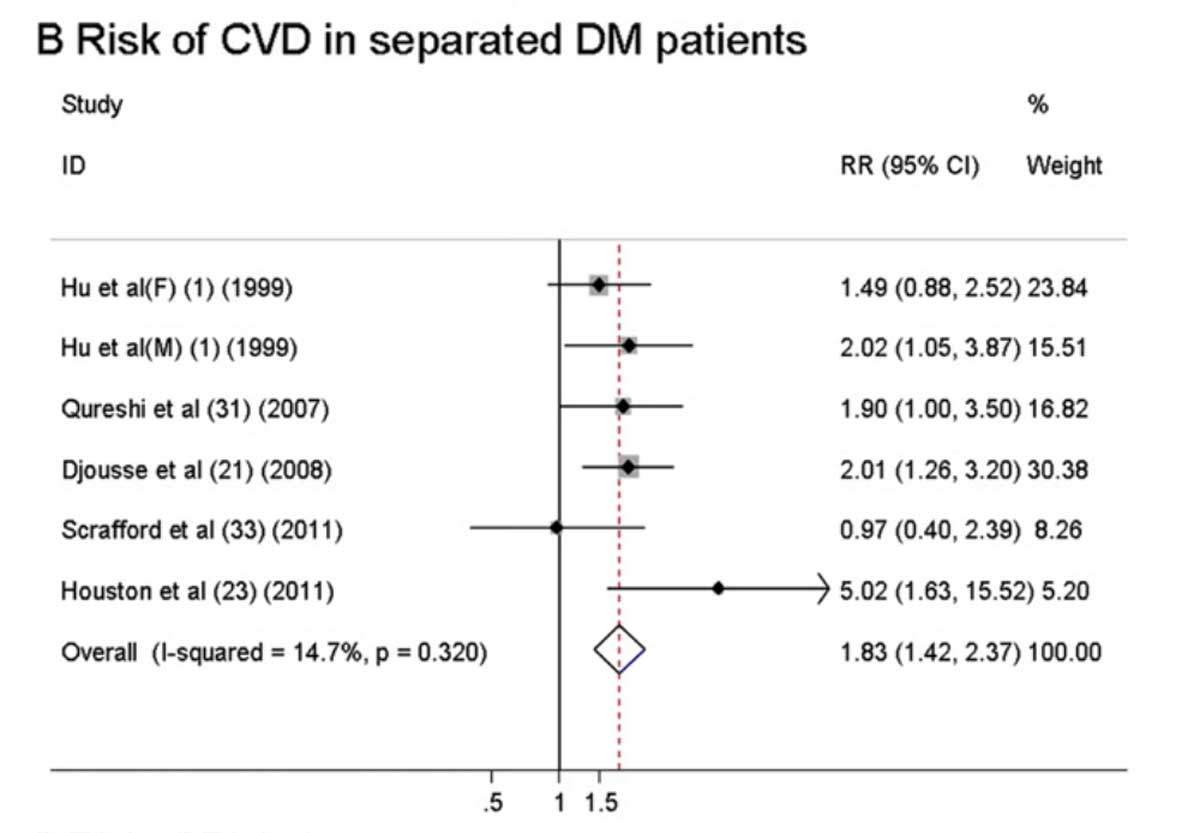

But remember, the question we're answering is, “are eggs smart or dangerous for people living with diabetes?” These researchers performed a subgroup analysis on subjects specifically living with diabetes, and they found something very different from the general population.

They found that men who ate 6 or more eggs per week doubled their risk of developing coronary heart disease. And women who ate more than 6 eggs per week, increased their risk for coronary heart disease by 49%.

Now, that's interesting, because it shows that when you've already been diagnosed with some form of diabetes, eggs go from being potentially harmless, to actually quite harmful.

Study 2 – Regular egg consumption does not increase the risk of stroke and cardiovascular diseases

The next paper was published in 2007 and found that eating more than 6 eggs per week does not increase the risk of stroke in people who had no pre-existing conditions at the beginning of the study. So we see the same thing between the first two studies.

But for those that are living with pre-existing diabetes at baseline, eating 6 or more eggs per week doubled the risk of coronary artery disease. Now, these results came from studying 9,734 adults, 349 of them who were living with diabetes. So it's the same pattern that we saw with the previous study.

So these first few studies imply that if you don't have diabetes, then eating eggs doesn't seem to increase diabetes risk. But if you are living with diabetes, then your risk for developing coronary artery disease and coronary heart disease increases significantly, as egg consumption increases towards 6 or more per week.

Study 3 – 2008 Physicians Health Study

In 2008, the Physicians' Health Study found that the consumption of more than 1 egg per day resulted in a 23% increase in the risk of all-cause mortality, which is premature death from any cause.

In this study, information on egg consumption was self-reported by the subjects using simple abbreviated, semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire – a food frequency questionnaire that asks them to report how often on average, they've been eating eggs during the past year.

Their responses include: rarely or never, between one and three per month, one a week, two to four, five to six per week, daily, or more than two eggs per day. This information was obtained at a baseline, and then at 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 months after they were randomized into one of their groups.

This study analyzed more than 21,000 participants over the course of 20 years. And they found that egg consumption of about six eggs per week was not associated with the risk of all-cause mortality, which follows from the previous studies. But the consumption of seven or more eggs was associated with a 23% increased risk of death after controlling for many confounders.

This is interesting because the data from the Nurses Health Study indicates that eating more than 7 eggs per week doubled the risk of all-cause mortality in male subjects and that eating more than 7 eggs per week increases the risk of heart disease in males living with diabetes.

These are very important studies because all-cause mortality is the ultimate risk factor when evaluating the effect of any lifestyle variable.

If your risk for all-cause mortality increases due to any single variable, it means that your risk for premature death increases significantly. And that’s important.

Here’s another way to think about all-cause mortality.

If I were to tell you that sleeping less than seven hours per night increases your chances of premature death by 20%, would you care?

If I told you that drinking more than two alcoholic beverages per day can increase your risk for premature death by 30%, would you pay attention?

Researchers discovered that eating 1 egg per day (or 7 eggs per week) doubles your risk for all-cause mortality when living with diabetes.

Study 4 – Physicians Health and Women’s Health Study

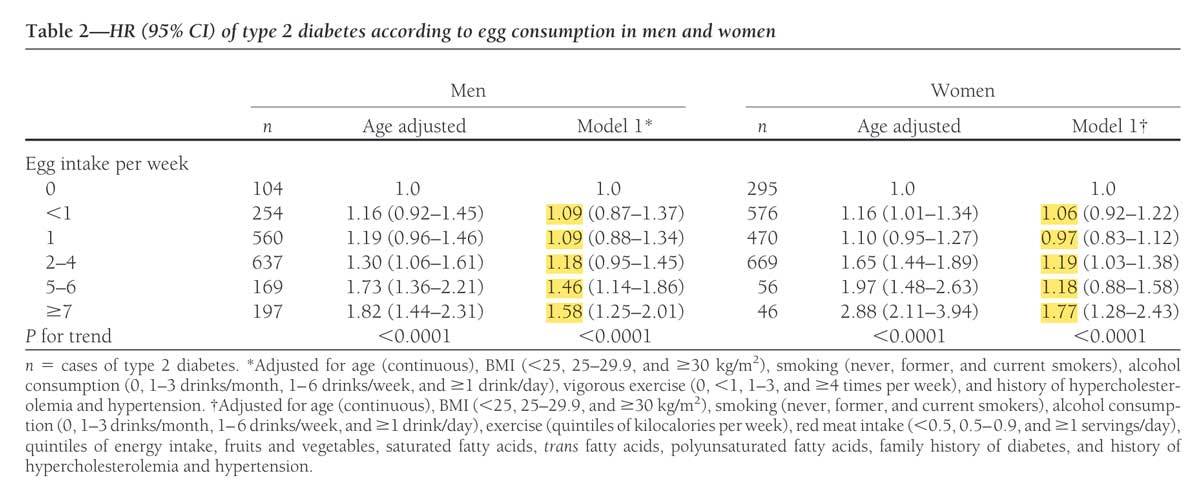

In 2009, researchers published a prospective study using data from the Physicians Health Study, which studied more than 20,000 male participants, and the Women's Health Study had a total of 36,000 female participants.

This study reported that eating 7 or more eggs per week increased the risk of developing type 2 diabetes by 58% in men and 77% in women.

This increased risk was also calculated after adjusting for potentially confounding variables such as age and BMI, whether they smoked/drank alcohol/exercised, and whether they had a history of high cholesterol or high blood pressure.

So once you take away all those variables, you can isolate whether or not eggs had any influence on type 2 diabetes risk or not.

And you can see that as the number of eggs per week increases, so does the risk of developing type 2 diabetes. For men, the risk of developing type 2 diabetes increases from 9–58% in a dose-dependent manner.

You can also see that women who ate less than 1 egg per week experienced a 6% risk of developing type 2 diabetes, increasing to 77% when eating 7 eggs per week.

This information is quite convincing because it shows that eating more eggs not only raises the risk for both genders, but that the risk also climbs quickly with increased egg intake.

Study 5 – The Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study

Let’s move to another study called the insulin resistance atherosclerosis study. This was also published in 2009, and it included 880 middle-aged adults who had no diabetes at the beginning of the study. After five years, 144 individuals developed diabetes. And all participants completed a 114 item food frequency questionnaire, which is very long and very tedious.

This study again showed a very clear positive association between egg intake and diabetes, one that was independent of confounding variables including age, sex, race, a family history of diabetes, glucose tolerance at baseline energy expenditure, smoking, and energy intake.

The goal was to isolate what eggs do to your risk for type 2 diabetes, and the results were clear:

People who ate no eggs or very few eggs were the least likely to develop diabetes, and people who ate the most eggs were the most likely to develop diabetes.

Study 6 – The Chinese Cohort Study

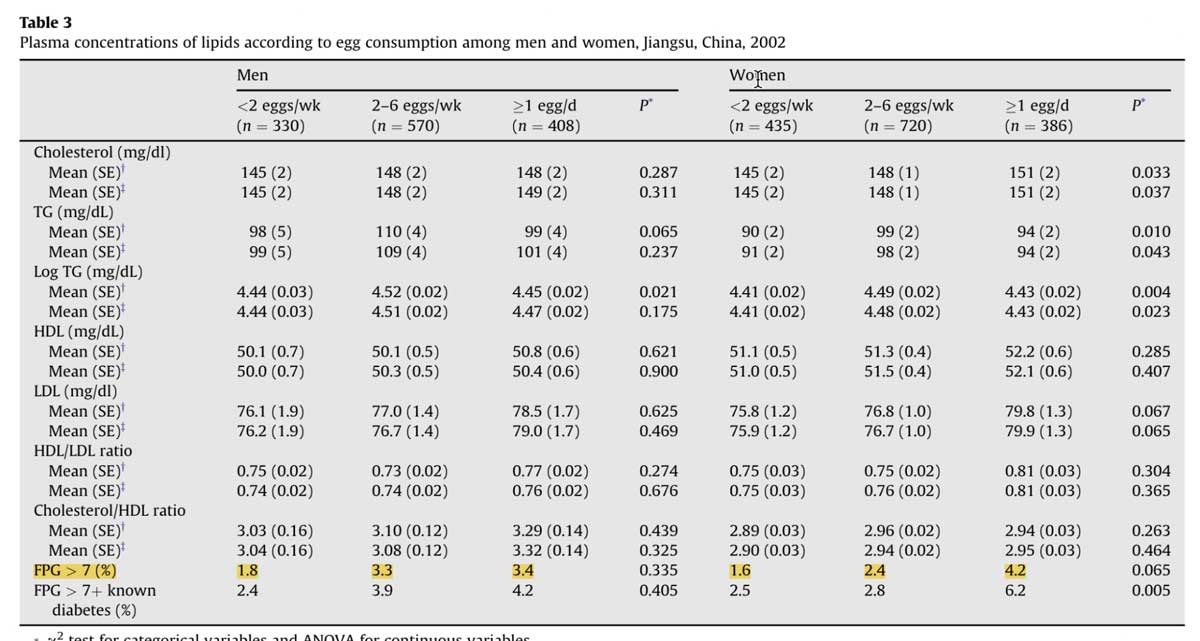

Next, we have the Chinese cohort study. In this study, researchers surveyed 2849 adults in China in 2002. Each study participant completed a food frequency questionnaire and provided three days of weighed food records, along with having their blood drawn and analyzed multiple times.

The results of this study were published in 2011 and demonstrated that there was a strong

link between egg consumption and diabetes risk remained, especially in women. Again, this association remained after adjusting for age, calorie intake, education, family history of diabetes, and sedentary behavior.

At the very bottom of the chart, the researchers measured fasting plasma glucose. When men's egg consumption increases (from 2 eggs per week to more than 1 egg per day), their risk of diabetes nearly doubles, from 1.8 to 3.4. In women, the ratio rises from 1.6 to 4.2 as egg intake increases.

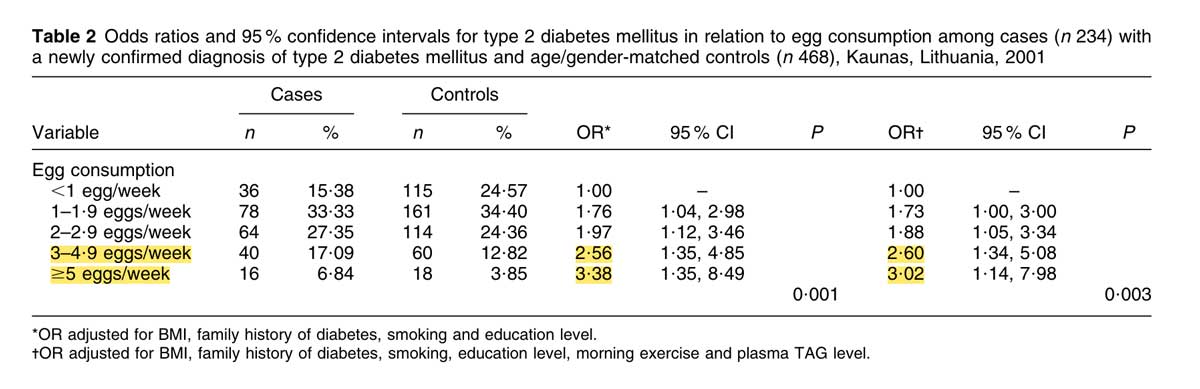

Study 7 – The Case-Control Study

Okay, the next study is the 2001 case-control study, performed in an outpatient clinic in Lithuania. The study included a total of 234 people who had all been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. In addition, 468 people who had not been diagnosed with diabetes were included in the study.

And after controlling for variables including BMI, family history of diabetes, cigarette smoking, education, morning exercise, and fasting plasma triglyceride levels, the researchers discovered the following:

There is a 2-fold increased risk of type 2 diabetes for individuals consuming 3-5 eggs per week

There is a 3-fold increased risk of type 2 diabetes in people who ate 5 or more eggs per week

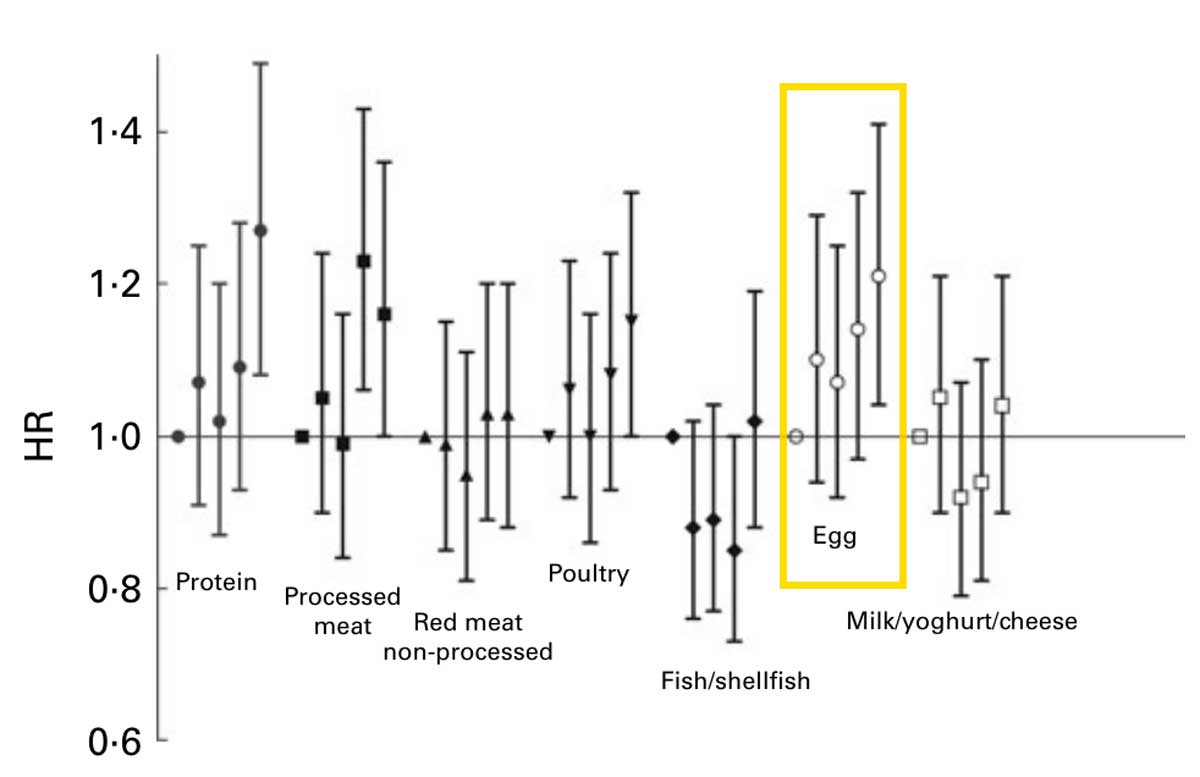

Study 8 – The Malmo Diet and Cancer Cohort

In the Malmo diet and cancer cohort, in Malmo, Sweden, researchers recruited 27,000 nondiabetic individuals and almost 1,000 individuals living with diabetes, and they ran them through a detailed questionnaire about their socioeconomic status, their lifestyle, and their dietary factors.

Specifically, the researchers investigated what happened to people who ate protein-rich foods, including processed meats, unprocessed red meat, chicken, fish, shellfish, eggs, milk, yogurt, and cheese.

Like the other studies mentioned above, this study also found that a high intake of eggs was linked with an increased risk of the development of diabetes. They determined that in 4 out of the 5 studies, increased egg consumption significantly increased the risk of developing diabetes.

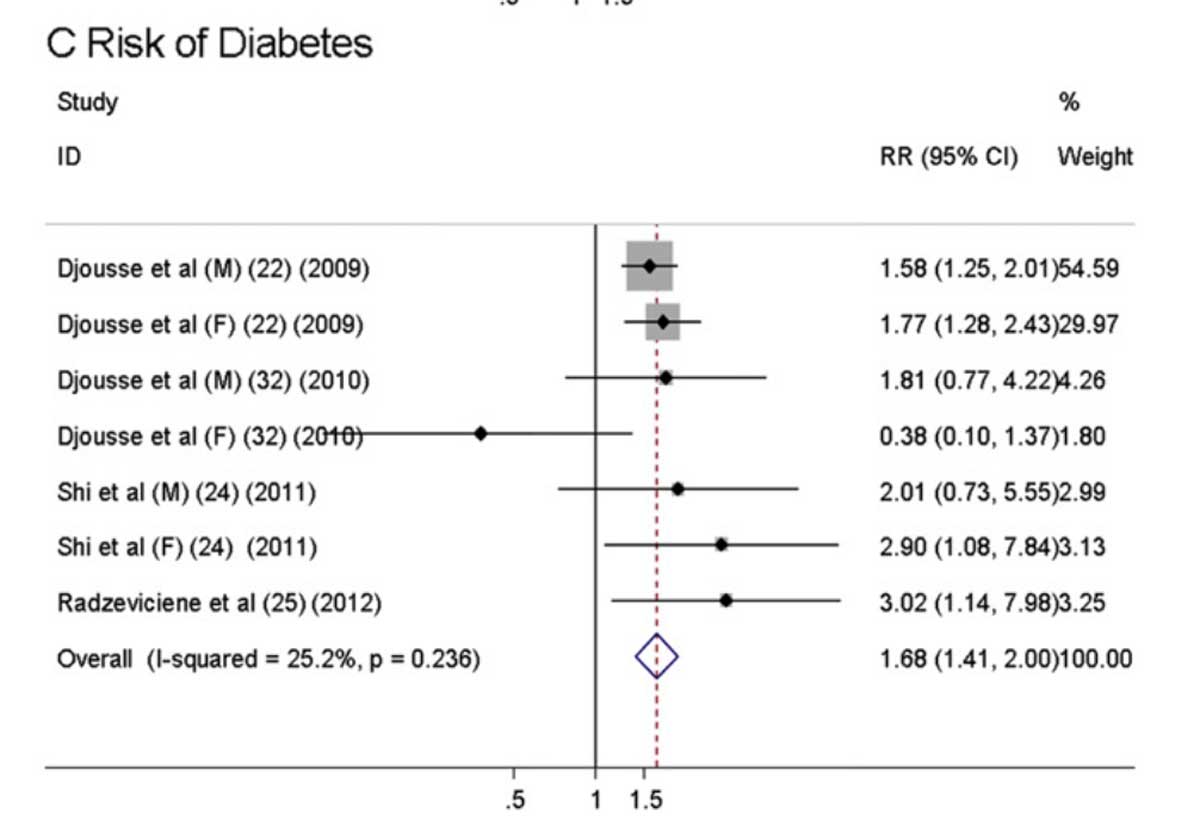

Study 9 – Cardiovascular Diseases and Diabetes Meta-Analysis

Here we focus on another meta-analysis, including 14 studies with over 320,000 participants.

Researchers discovered that egg consumption increased the risk of diabetes in a dose-response manner, which suggests that as you increase your dose, the magnitude of the effect correspondingly increases.

High egg consumption was associated with a 68% increased risk of diabetes, and the dose-response analysis showed that for each egg consumed per week, the risk of developing diabetes increased by 29%.

According to this study, the risk of developing diabetes increased by 55% for those who ate the most eggs.

That’s a lot of Science! And There’s Even More!!

Often, you’ll hear people say that there's no evidence/ insufficient evidence to indicate that there's a correlation between egg consumption and diabetes risk, or between egg consumption and cardiovascular disease risk and people living with diabetes.

As you can see above, there is a wealth of scientific data. And we have seen in both small-scale studies and large-scale studies that the data trends in the same direction.

Getting the Full Picture on Eggs

Our analysis of the research suggests the following:

If you do not have pre-existing diabetes, your risk for developing type 2 diabetes increases as your intake of eggs increases.

In nondiabetic individuals, increasing egg intake from 0 eggs per week to 1 egg per day increases the risk of developing diabetes by 58%.

If you are living with pre-existing diabetes, eating eggs is more detrimental to you than the average nondiabetic individual.

The higher your egg intake, the higher your fasting blood glucose, risk of stroke, risk of a heart attack, and risk for premature death from any cause.

Therefore, regardless of whether you're living with diabetes, eggs are not considered a “safe” food by any means.

What’s more important is that if you are living with diabetes, then your risk for the development of other complications increases significantly as your egg intake increases, in a dose-dependent manner.

The Final Word on Eggs

Many studies, including meta-analyses, systematic reviews, case-control studies, and large-scale epidemiological studies, all point in the same direction.

Eating eggs increases your risk for the development of type 2 diabetes, heart disease, diabetes complications, and all-cause mortality. To maintain a low risk for these conditions, limit your egg consumption as much as possible.

It's essential to bear in mind that eggs might not be as safe for you as you may think. There's a wealth of scientific evidence to indicate that your risk for chronic diseases and all-cause mortality increases with increasing egg intake.

Whether you are currently living with diabetes, consuming eggs can significantly elevate your risk for developing diabetes-related complications, and it's important to acknowledge this in order to make informed choices about your dietary habits.